Why Social Innovation Matters

Judith TERSTRIEP

|

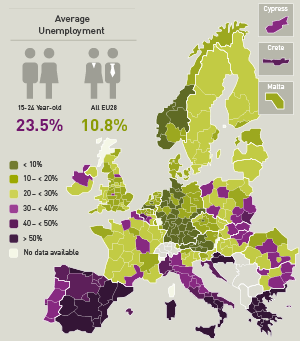

Europe is confronted with many complex and interrelated socio-economic challenges and these have clearly been exacerbated by the recent economic crisis. Long-term GDP growth in the EU27 is projected to fall from 2.7% before 2008, to 1.5% up to 2020, a slight rebound to 1.6% for 2021 to 2030 and a slowdown to 1.3% for 2031 to 2060 (EC 2012c). Unemployment has risen in almost all parts of the EU and is expected to remain at high levels in several Member States up to 2018 (EC 2014, IMF 2013). As illustrated in Figure 1, youth unemployment has reached 25% and more in 13 Member States (EC 2012a, 2012b). Structural changes in the labour market including deregulation and the rise of temporary contracts combined with poor educational attainment increase the risk of marginalisation for young people. Likewise while women still form the majority of the employed, they perform most part-time and unpaid jobs (EC 2013a). At the same time an ageing population results in rising costs linked to pensions, social security, health and long-term care. As a consequence, welfare costs are rising dramatically while governments all over Europe are affected by major budgetary constraints. Technological innovation has long been considered the primary driver of economic growth and competitiveness, the core of the «knowledge economy» vision that has inspired European policymakers since at least the 1990s. Building on the European social model, policymakers have sought a high growth strategy that achieves convergence with high levels of social and economic inclusion. A period of technological growth culminating in prolonged recession has led to a pattern of uneven social and economic development in which restructuring has benefited some while leaving others far behind. A distinctive kind of innovation is needed, one whose patterns and participants differ from a purely profit-oriented economic paradigm. It is about ways of fostering innovation that, complementing technological progress, achieves true convergence between economic growth, sustainability, inclusiveness, equality and diversity by realising the innovative and productive potential of society as a whole, including those currently perceived as an economic burden. This is where social innovation comes into play. Creating a socio-economic system capable of understanding and generating effective social innovations represents a major policy challenge for Europe and its regions in the coming years. |

|

|||

|

SIMPACT, with its twelve partners from ten European countries aims at understanding the economic foundation of social innovation targeting marginalised and vulnerable groups in society. |

SIMPACT Project |

|||

|

Social innovations are believed to empower these groups in creating the organisational infrastructure, improved access to finance (e.g. micro-finances, mobile financing) and personal support required to strengthen their position within the labour market, enable the creation of business ventures or enhance welfare and social integration. Social innovation is thereby believed to realise its potential contribution to smart and inclusive growth to the extent it can (re -) engage vulnerable populations as untapped economic resources. Moreover, it is assumed that from an economic perspective unfolding this untapped potential is more efficient than continuously subsidising these groups while leaving them in their constrained situation. However, several key issues have to be addressed before social innovations can fully be mainstreamed into the European economic sphere and its policy environment. We need:

|

Social innovation refers to novel combinations of ideas and distinct forms of collaboration that transcend established institutional contexts with the effect of empowering and (re-)engaging vulnerable groups either in the process of social innovation or as result of it. Modelling and testing will validate the developed concepts, tools and instruments and help stakeholders to better cope with social innovation related uncertainties. A continuous stakeholder dialogue through stakeholder experiments, policy dialogue workshops and action learning sets, indicator labs and think tanks will facilitate learning and processes of co-creation by integrating actors' views into SIMPACT's research activities. |

|||

|

This is were SIMPACT comes into play. The project systematically investigates the economic foundation of social innovation in relation to markets, public sector and institutions to provide a dynamic framework for action at the level of individuals, organisations and networks. Economic foundation in the here uses sense is not interpreted as economisation of social innovation limited to, for example, questions of market efficiency. |

Economic underpinning is about economic principles, objectives and components that make social innovation successful in terms of economic and social value. |

|||

|

SIMPACT's theoretical and empirical work is framed around the following focal research questions that fundamentally affect social innovations' potential and scope plus its economic and social impact:

|

From Roots to Results |

|||

|

To answer the hitherto open research questions SIMPACT combines integrating critical analysis of current and previous work on social innovation with future-oriented methodologies, new actionable knowledge and continual stakeholder participation. SIMPACT's multidisciplinary theoretical and methodological concept advances knowledge and the state of the art by linking the theoretical foundation of the economic dimensions of social innovation in the interaction of markets, public sector and institutions with the collection of empirical evidence through theoretical informed analysis - from general meta-analysis to business case studies and social innovation biographies. These will be be translated into stronger social innovation concepts facilitating improvements for spread and growth plus methods, tools and instruments supporting social innovation stakeholders. This includes indicator sets to measure social innovations and tailored methods to evaluate social and economic impact, plus enhanced modes of policy production, policy instruments and guidlines. Modelling and testing will validate the developed concepts, tools and instruments and help stakeholders to better cope with social innovation related uncertainties. A continuous stakeholder dialogue through stakeholder experiments, policy dialogue workshops and action learning sets, indicator labs and think tanks will facilitate learning and processes of co-creation by integrating actors' views into SIMPACT's research activities. Accounting for the diversity of welfare regimes across Europe, including New Member State specificities will ensure tailored, actionable deliverables. Eight high profile associate partners - namely ASHOKA, DESIS, UNECE, ENoLL, MindLab, SozialMarie, Forum PA and European Business Summit - will help ensure the success of SIMPACT's dissemination activities. |

References European Commission (2012a). European Economic Forecast, Autumn 2012. Brussels: DG for Economic and Social Affairs: Commission Staff Working Paper. European Commission (2012b). Youth Unemployment: Commission proposes package of measures. Press Release, IP/12/1311, 05/12/2012. European Commission (2012c). The 2012 Ageing Report. Economic and budgetary projections for the 27 EU Member States (2010 - 2060). European Economy, 2(2012). European Commission (2013a). Employment - Still a huge gap between the sexes. European Research Headlines, Brussels, DG Employment, Social Affaires and Inclusion, 18 January 2013. European Commission (2014): Investment for jobs and growth. Promoting development and good governance in EU regions and cities. In: Dijkstra, L. (ed), Six report on the economic, social and territorial cohesion, Brussels, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, June 2014. IMF (2013). World Economic Outlook, April 2013. Hopes, Realities, Risks. International Monetary Fund: World Economic and Financial Surveys. |

Public Policy Implications of Social Innovation

Judith TERSTRIEP & Peter TOTTERDILL

|

Policymakers from regional, national, EU levels of governance from across Europe met in Brussels to discuss social innovation's challenge to traditional policymaking. Organised by the University of Bath and hosted by Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), workshop participants shared experiences of the challenges and opportunities posed by social innovation, and the scope for transforming traditional modes of public intervention and regulation. The interactive session facilitated by Peter Totterdill focused on the emergence of new modes of policy production and delivery capable of unleashing the full economic benefits of social innovation. Agnès Hubert, author of the highly influential BEPA report on social innovation in the EU Empowering People, Driving Change set the scene with an account of the continuing rise of social innovation to policy prominence. Peter Totterdill warned that traditional approaches to policy design and implementation can constrain social innovation and stop it reaching its full potential. Experience of how New Public Management's regulatory and contractual focus can drive out innovation was widely shared, though some inspiring cases of policy innovation also came to light. Evidence can be found of efforts to create latitude within New Public Management regimes to overcome these rigidities. For example, national policy imperatives are a powerful driver for the outsourcing of local government services in the UK. Policy practices focused on the enablement of social innovation are emerging in many parts of Europe but are not yet well defined and understood - and this remains a key task for SIMPACT. Participants themselves shaped the rest of the agenda, drawing on a rich and diverse range of experience. |

Example Devon County Council's Inclusive Communities programmeThe programme avoided standardised social services delivered by private sector providers in rural areas. The Council's approach combines: (1) capacity building, working with community organisations to increase their ability to identify and meet need using local people; (2) providing individuals with personal budgets to enable them to commission bespoke services from local community sources. |

||

|

A lively group discussion on «Effective Engagement with Stakeholders & Citizens» identified trust, risk taking, leadership and community capacity as core characteristics of an effective relationship. Cooperation with citizens, NGOs, entrepreneurs and other social innovation stakeholders must be meaningful and fair. At the same time policy and decision makers need a clear understanding of when to engage with whom and for what purpose. Educating policymakers about social innovation and its importance for future development was discussed as a first step towards Integrating Social Innovation in the Structural Funds. Specific suggestions included the use of a balanced score card methodology to develop a joint vision and shared strategy among stakeholders. Enhancing the visibility of social innovation through, for example, the dissemination of case studies as a learning resource, pilot projects and improved communication were also explored. Access by practitioners to actionable knowledge is seen as key success factor. Sustaining the dynamics of social innovation was identified as another core challenge for policymakers seeking to create the conditions for social innovation to flourish and achieve maximum impact. But does a focus on sustainability challenge the innovative nature of social innovation? Participants agreed that an enabling environment for creativity is required, allowing for experimentation and shared learning. This includes a virtuous circle of research and evaluation, planning, acting and doing. |

Effective Engagement |

||

|

The «Performance and Governance» session began with a discussion of impact measurement - should outcomes be measured in terms of their utility to target groups (use value) or their market worth (exchange value)? What types of organisational and regulatory systems and procedures are needed to build an approach to measurement that it truly relevant to social innovation? Systems and procedures shape the behaviour of actors and stakeholders with in the triad of markets, public agencies and NGOs, thereby influencing the scale and outcomes of social innovation. |

Performance & Governance |

||

|

The Brussels workshop was just the start of a dialogue that will continue throughout the life of the SIMPACT project. Ideas and experiences from the workshop are contributing to the production of a White Paper on «The Policy Challenges of Social Innovation» which will be widely distributed amongst Europe's social innovation communities. If you are interested in joining the policy dialogue, please visit SIMPACT's Visit LinkedIn group LinkedIn group . |

Participate! |

Vulnerable People's View on Social Innovation

Bastian PELKA & Christoph KALETKA

|

SIMPACT's first stakeholders workshop took place in Brussels. Twelve experts, representing stakeholders of vulnerable people in Europe, social innovators, research entities focussed on social innovation and policy makers in the field of social policy, came together on 30th September 2014 in Brussels. The aim: contrasting the project's initial desk research on economic underpinnings of social innovation with the experts' «hands on» perception. In a half-day workshop, Dr. Christoph Kaletka and Dr. Bastian Pelka from TUDO and Dr. Mehtap Akgüç from CEPS facilitated discussions with experts representing as different organisations as the Red Cross, Eurodiaconia, the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants or the European association of telecentres. They all share the mission to provide aids and empowerment for vulnerable or excluded people and see social innovation as one of their core practices. |

Engaging the Target Group«Social innovation strongly builds on a co-operative eco-system of social innovation that brings together policy makers, research, civil society and economy», says Dr. Bastian Pelka from sfs at TU Dortmund. «And this expert workshop brought them all together to identify drivers and barriers for social innovation.» |

||

|

The workshop produced a collection of drivers for social innovation which articulates a strong will of «the field» to provide social innovations. This will is driven by the individuals' perceptions of (either individual or societal) needs. From the stake holders' perspective, the strongest driver for social innovation is the rise of social needs that is brought by economic crises, governmental fail or human emergencies. Speaking in economic terms, this market seems to have both: a supply of innovation and a demand. Both are working as drivers. The preliminary analysis also shows an insight into the functioning of this «market»: a cooperative and communicative environment, including the quadruple helix of actors - seems to build the backbone of social innovation activities. A good connection of these actors and a productive use of communicative infrastructure - quite often via social media - seems to be essential for the growth of an eco-system of social innovation. Barriers are often related to the eco-system of social innovation: The professionalisation and available resources of (potential) innovators, the knowledge offered by researchers, the communication and cooperation within the eco-systems and conflicts of interest within it. Actual cash-flow was surprisingly rarely mentioned as a barrier - this might be interpreted as the modus vivendi in traditionally low budgeted systems. Barriers seem more often to come from missing communication, co-operation or too rigid thinking in an actor's own logic. |

Drivers & Barriers

|

||

|

After the identification of drivers and barriers of social innovations, the participating experts were invited to combine the identified aspects to construct a grounded scenario of «how to most effectively block social innovation in society». This challenging change of perspective produced those barriers that the participants are facing in their practice: Missing co-operation, even contradictory legislation and a «silo thinking», caging necessary supporters in their own system's logic. Seeing all actors' activities in this scenario together, the main approach to block social innovation is to stay in each actors' own logic - in a silo of own perceptions. If policy tries to steer in a «safe» way that is not «disturbed» by external influence; economy tries to gain short impact, research avoids the risk of investing in this new field and society applies risk-aversion by the reason of saving existing practices, each actor will stay in its inherent logic. Hence, the eco-system of social innovation builds on co-operation of these actors, leaving their own fields of interest. |

Grounded Scenario |

Connecting Social Innovation with the Territorial Developement of the Champagne Ardenne Region

Interview with Jean-Paul Bachy, President of the Conseil régional Champagne-Ardenne

Melissa BOUDES

|

|

3rd European Summer School of Social Innovation

Exploring Innovation and Social Innovation in the Public Sector

Mercedes OLEAGA & Javier CASTRO SPILLA

|

Last July, the III European School of Social innovation was held in San Sebastian (Basque Country, Spain). The European School of Social Innovation was created in 2011 and is run by the ZSI, Austria, the Social Research Center of the Technical University Dortmund (Germany), and Sinnergiak Social Innovation Center (Spain). The 2014 summer school was organised by SINNERGIAK SOCIAL INNOVATION with the collaboration of Innobasque (Basque Agency of Innovation-Spain) and SIMPACT European project. In this edition, the main objective was to offer a plural view about innovation and social innovation in the public sector. This Summer School offered two perspectives:

|

The Concept |

||

|

The Summer school was split up in two sections/days; the first one focused on the different discourses on innovation and social innovation linked to the public sector in the international scene, and the second one focused on the Basque most interesting cases. The multidisciplinary of the speakers and the audience made possible a rich debate within some questions and certainties were produced. Some questions raised up:

On the other hand the certainties results from the debate were:

|

SI in Public Sector

|

||

|

The speakers and the debate also caused several reflections concerning social innovation in the public sector. The first consideration is related with what is social/public innovation. At the moment, innovation is considered as an economic product composed by products and markets that leads to the economic development, but, we are moving to a new approach of innovation, innovation as social/public concept oriented where the citizens needs and the improvement of the quality of life are central issues that drives to social development. The consequence of this change is that the concept basis and contents are being re-defined. |

Social/Public Innovation |

||

|

The second reflection is about what means innovation in the public sector. Two different perspectives are shown. On the one hand, the external perspective, where innovation is promoted in the territory, is financed and innovation strategies are established, and on the other hand, the internal perspective, where it is related with structure, services management and with the external stakeholders relationship. |

Innovation in Public Sector |

||

|

Another issue raised during the Summer School is who are the innovation actors at the Public sector. Again, a dichotomy is found. The group of institutional entrepreneurs, on one side, composed by policy leaders and policy managers; and the group of social entrepreneurs on the other side, constituted by social stakeholders and agencies, cultural stakeholders and agencies, and economic stakeholders and agencies. |

Innovation Actors in Public Sector |

||

|

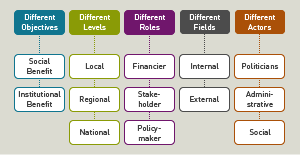

Objectives, processes and results are important issues for social innovation in the public sector. Related with objectives fours aspects have been taken into consideration: expenditure rationalization, sector limitation, change process and results, and encourage social cohesion. Talking about process, orientation, participation, collaboration and governance are key concerns. Finally, as results, social benefits, institutional benefits and the measurement of results (making tangible the intangible) are essentials. Finally, and having in mind the need of a conceptual balance, the following chart is presented. The chart presents the need of balance within different social innovation in public administration dimension. |

|